Blind Trust: 5 Steps to Tackling the Anonymous Messaging Problem

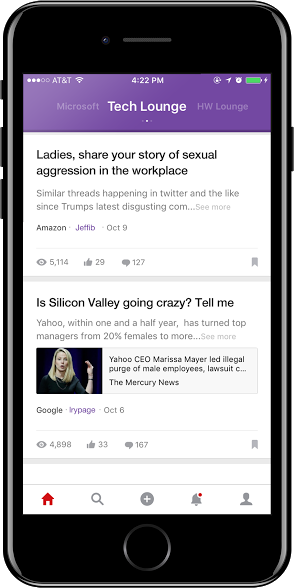

FEATURED IMAGE | Source: Teamblind Inc.

When we started development on Blind last year, we faced a pretty daunting challenge: a number of other anonymous messaging apps such as Secret had already enjoyed a brief vogue in the Valley, only to flame out amid controversy over hateful or poisonous comments which quickly choked their boards. For 12 years running, no company has successfully managed to quite overcome Penny Arcade & John Gabriel’s Greater Internet F — -wad Theory. Consequently, even successful anonymous apps and messaging boards still struggle with a reputation for encouraging harassment or worse.

All of which leaves people in tech wary to try another one — let alone admit to others in tech when they do. In fact, a Facebook employee recently told me that Mark Zuckerberg directly addressed the topic in a company-wide meeting, saying he was “disappointed” that Facebook’s own staff would use an anonymous app for name-calling when Facebook itself is supposed to be about advocating open culture and connecting people.

Despite all that, we’re convinced there’s something powerful about online anonymity — if it can be properly cultivated. Anyone who’s participated in a friendly and thoughtful conversation on a pseudonym-driven site like Reddit or Hacker News knows this. And while everyone wants their company to succeed, that requires a forum where truly honest conversations can emerge in the midst of hierarchy and professional barriers. And that capability means maintaining some level of anonymity.

We are still honing Blind, we believe we’re close to reaching that goal. Here’s what we’ve done so far:

Wrap Individual Identity Around a Company

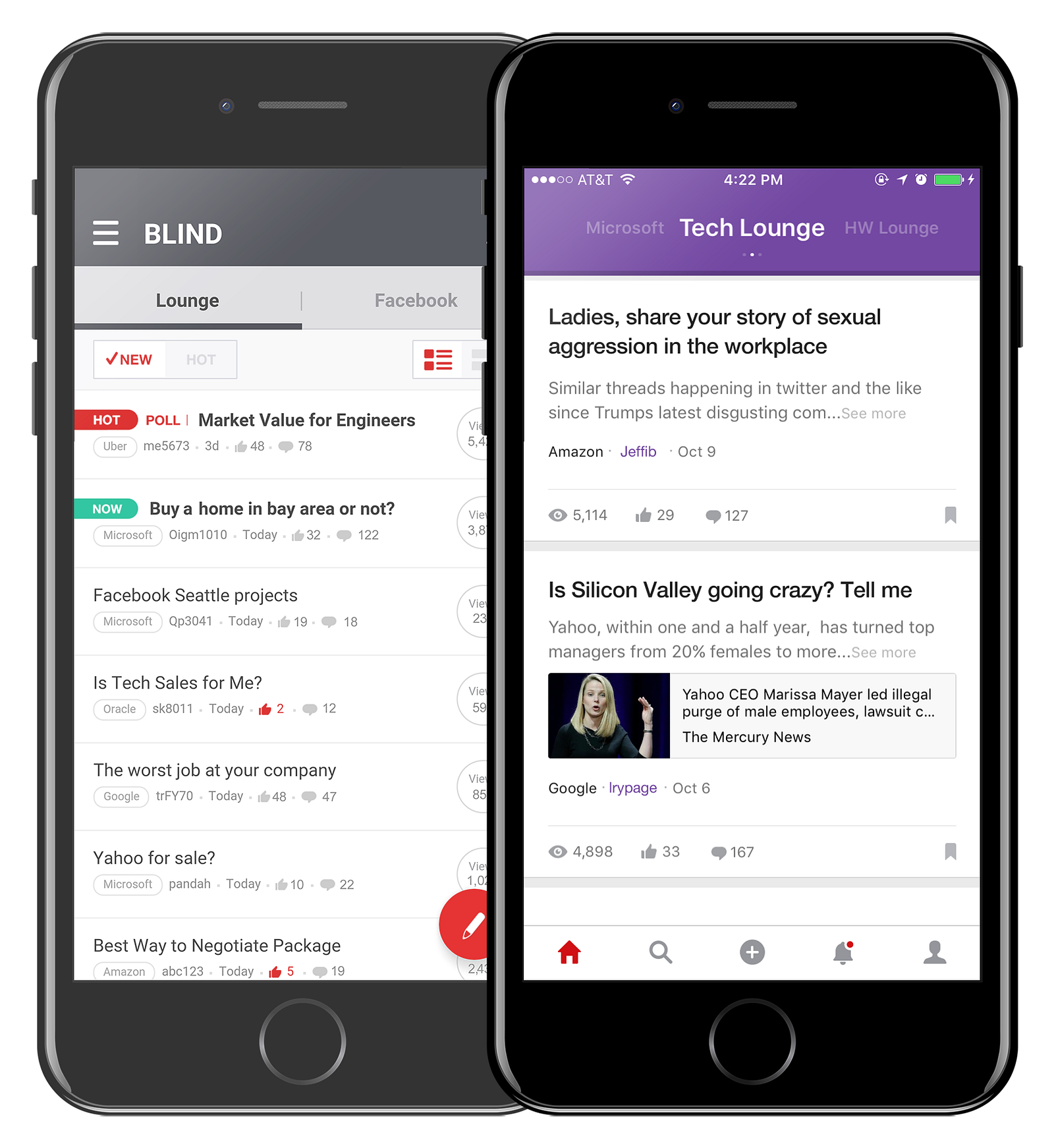

Our first step was to keep all users’ identities anonymous — but bind their usage to the company they work for. This is why users can only access Blind if they register through their company name, which then places them in a Blind forum reserved for fellow staffers. Our users are anonymous, but their company information is always public. This imbues a broader sense of identity on each individual user, and an expectation of integrity to what they write. Usernames (which users can change as many times as they like) then exist not to identify who each person is behind the keyboard, but become a fun way of expressing their personality.

Cultivate Community Within a Company — and In That Company’s Industry

Grouping Blind users by company immediately creates a context for conversation. If you log in for the first time during lunch, and there’s an anonymous conversation there about that morning’s all-hands meeting, you are going to read it.

Airbnb, Amazon, and Microsoft have a Tech Lounge to share. Wherever a user works in tech, there’s probably something intrinsically interesting in reading about another user who, say, left Facebook to work at Uber, and shares their experiences with each firm. We often see users in the Tech Lounge comparing notes, asking how much others in the same position are paid, or how women in the company are treated. That’s how community starts.

Establish an Upfront Voice

“Voice is important”: This was the lesson I took away during coffee with an executive with a popular, anonymous messaging app. New users look for language or characteristics they can relate to. YikYak’s 30-mile radius, which insured people at the same college would see each other’s messages, was their sauce for success. At Blind, when we launched our service for Amazon employees, we purposely geo-fenced out all of the fulfillment centers — at first. Amazon employs tens of thousands of part-time and full-time employees in these centers, and have a work life far removed from Amazon HQ and staff working at AWS, Retail, Prime, etc.

Once we had a community of Amazon users established among this cohort, we gradually started marketing Blind to other offices and, finally, fulfillment centers. This ensured that new users are introduced into the existing “voice”. In essence, our belief is this: the kind of conduct and conversations that the first 100 users at a given company engage in defines the lifetime voice of that community.

Flagging Bad Behavior — and Flagging Bad Flagging

Our flagging feature for users, enabling them to request removal of objectionable content, took (and takes!) a lot of time to get right. But it was crucial that we did: Anonymity is almost always associated with bullying or trolling. We want a virtual community which rewards honesty, and while it might include venting and light trolling from time to time, gives more weight to active users who want a positive experience. So if an individual gets too many flags, they’re booted from the app. Being regular Redditors, we also know how often flagging systems themselves are abused, and built-in algorithms to deal with this. So for instance, someone who has been active without flags might carry more weight when they flag content, compared to a flagger who logged in for the first time yesterday. As our user base grows, we constantly tweak our weighting system to ensure that each community controls what is discussed in their space.

Brighter UI, Happier Comments

We learned a pretty important UX design lesson after launch. At first, our app’s visuals (like many other anonymous apps before us) had a dark, cloak-and-dagger vibe. In a recent update, we decided to do a complete 180°, changing the layout to have lots of clean white space. To our surprise, the number of “flagged” comments/posts immediately dropped by ~10–15%, while the number of total page views and new posts have increased. Users, in my opinion, profoundly react to design language — especially in an anonymous context.

Succeeding While Blind

So far our approach seems to be working: After a year in US app stores, 1 in 4 employees at Yahoo, 1 in 5 employees at LinkedIn, 1 in 6 employees at Microsoft and 1 in 10 employees at Uber are now using Blind. We have thousands of active users from Google, Facebook, and Amazon as well.

I was in a meeting with a CEO of a well-established Valley company recently, and to my surprise, discovered he himself was a regular user.

At first, my feelings were hurt by some of the things my employees brought up [on Blind], but two weeks in, I realized how much I was learning about their needs.

Now he checks the app a dozen times a day.

We knew we were on the right track when top executives and not just employees started using our app. At its core, Blind is for everyone in an organization. We don’t optimize our app based on data and dashboards, but based on the health of the user community — how it helps make work more human, connect coworkers on mutual interest, managers, and human resources all together in an even playing field.